Introduction

Respiratory infections carry a huge financial burden to UK farmers. There are multiple viral causes of pneumonia which we will discuss.

What causes viral pneumonia in cattle?

The important viral causes of respiratory disease are: infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) and bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV). Parainfluenza-3 virus (PI3) is much less important. Bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVD) can also cause respiratory disease. BVD and IBR are also discussed in more detail elsewhere.

Disease caused by infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus.

These viruses can cause disease by themselves, or damage the defence mechanisms of the upper respiratory tract and predispose to secondary bacterial infections of the lungs. There are a large number of bacteria that can cause either primary lung disease or secondary to viral compromise of the lung defence mechanisms.

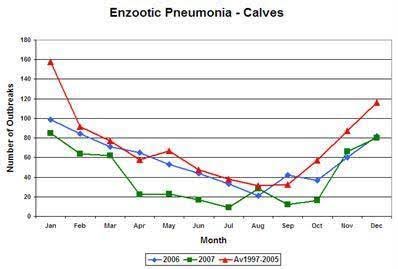

Seasonal nature of bovine respiratory disease in the UK.

This graph shows the seasonal nature of calf respiratory disease in the UK. Most outbreaks of respiratory disease occur within one month of housing in the autumn and early winter. Autumn-born calves are generally more severely affected than older spring-born calves. This is due to the increased likelihood of adverse weather conditions and housing of animals.

Respiratory disease in beef cattle is multifactorial. The interaction between the various infectious agents (whether bacterial, viral or both), the environment, and immunity of the individual calf all play a part in the respiratory disease puzzle. Adult cattle provide an important reservoir of many respiratory tract pathogens. When animals are kept in close contact to one another, these viruses can easily be passed from one animal to the other.

What are the economic and welfare impacts of viral pneumonia?

In 2025, bovine respiratory disease is expected to cost the UK cattle industry an estimated £50 million annually. This makes it the most significant reason for death and poor performance in young cattle, particularly in calves. The cost includes both immediate treatment expenses and the long-term impact on productivity due to reduced growth rates, increased days to finish, and decreased milk production. Often large numbers of animals in a group are affected, having a protracted convalescence period and so respiratory disease is a major animal welfare concern

What are the clinical signs of viral pneumonia and how can it be diagnosed?

Viral pneumonia is most typically seen in weaned calves that are housed in poor environmental conditions. Store cattle can become infected with respiratory pathogens at the time of purchase from markets. Clinical signs generally first start to appear 2-3 weeks following housing.

The severity of clinical signs can vary, ranging from mild illness with only a small amount of clear nasal discharge to severely ill animals. These severely affected animals do not eat, they are depressed, slow to rise, and stand with their head lowered. A high rectal temperature, ocular and nasal discharge, and coughing are common signs. Some severely affected animals may be found in respiratory distress with mouth-breathing and rapid abdominal movements. There can be a purulent discharge from the eyes and nose, usually in more chronic cases, with a secondary bacterial infection. In severe outbreaks, some animals die.

In the case of Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR), in addition to the clinical signs mentioned above, an infectious pustular vulvovaginitis (IPV) in females or infectious balanoposthitis (IPB) in bulls can also be seen.

Clinical signs caused by IBR generally first appear two to three weeks after a stressful event. During an outbreak of IBR, the morbidity rate may be 100% but the mortality rate is generally less than 2%. The first two or three cattle affected often develop the most severe clinical signs.

Clinical signs caused by Bovine Respiratory Syncytial virus (BRSV) are highly variable from no noticeable signs, to severe disease and death. Parainfluenza (PI3) doesn’t tend to cause severely ill animals on its own, but predisposes the lungs to secondary bacterial infection.

Disease caused by bovine respiratory syncytial virus.

Auscultation (listening to the lungs with a stethoscope) is considered a critical component of the veterinary clinical examination for the diagnosis of bovine respiratory disease. However, studies have shown that a stethoscope detects only around 5 % of cattle with lung changes

Laboratory confirmation may be necessary before embarking upon a vaccination protocol in the face of infection, and to prevent a similar problem during the following year. Diagnosis of viral infection may involve taking eye and nose swabs, collection of lung fluid (broncho-alveolar lavage) and collection of 2 blood samples 4 weeks apart. Post mortem examination is only useful in cases of sudden death.

Measuring bulk milk antibody levels can be a very useful means of determining IBR status of the herd. However, a negative bulk milk result does not necessarily indicate that a herd is IBR-free as up to 20% of the milking herd can be latently infected with IBR before the bulk milk result will become positive, therefore blood testing is essential to confirm IBR-free status of a herd.

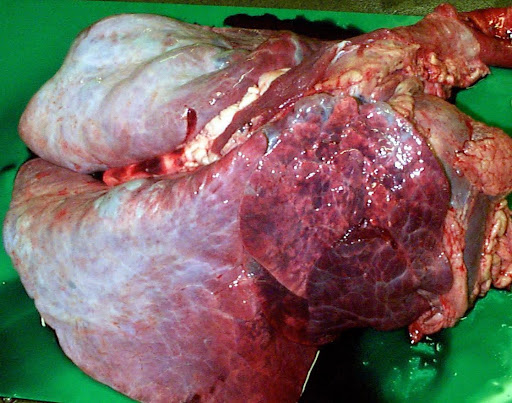

Post mortem examination is only useful in cases of sudden death (in this case BRSV infection).

An accurate diagnosis of the cause(s) of respiratory disease is essential so that the correct treatments are given and steps can be taken to prevent future disease using appropriate vaccines.

Visual assessment for signs of respiratory disease, such as a cough, nasal discharge and depression are unreliable and fail to detect all diseased cattle.

How can viral pneumonia be treated?

It is essential that the vet is contacted as soon as disease is suspected because the first cattle affected are often the most severely affected. Accurate diagnosis, treatment, and timely vaccination are essential to prevent further losses.

Viruses cannot be treated with antibiotics. Supportive treatment is given where necessary. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs are usually indicated in cases with a high temperature. They help bring the temperature down and speed up recovery. Dehydration should be treated in severe cases.

Secondary bacterial invasion of the damaged respiratory tract frequently occurs, which makes treatment difficult. In many situations, selection of cattle for treatment based on raised rectal temperature is the most cost-effective practice. All rectal temperatures and treatments are recorded and checked the following day to monitor response. This not only saves the cost of unnecessarily injecting healthy animals, but it reflects responsible use of antibiotics on your farm.

Antibiotic selection is very important and will be carefully considered by your veterinary surgeon. Antibiotics won’t treat disease caused by viruses, but it can prevent or treat a secondary bacterial infection, depending on which pathogens are causing disease on your farm.

How can viral pneumonia be prevented?

Respiratory disease is best prevented by a combination of good management, appropriate building design and ventilation, and effective vaccination programme against the major pathogens on that particular unit well before the risk period. The selection of an effective vaccination strategy will form an important part of the herd health plan drawn up in conjunction with the farmer's veterinary surgeon.

Maintenance of disease-free status is possible for closed herds, but viruses can be transmitted by direct contact over fences etc. from neighbouring farms. Isolating and vaccinating all purchased cattle before they are introduced to the rest of the herd can help as well.

There are a huge number of vaccines widely used to control viral respiratory disease and veterinary advice should be sought for the most appropriate prevention strategy. Vaccine can be injected prior to the anticipated challenge period (e.g., housing). Single intranasal vaccination may be helpful in the face of a disease outbreak. PI3 vaccine is combined with BRSV, with or without IBR, BVD and Mannheimia haemolytica. Many different combination vaccines are available, so you can choose the one that best reflects the diseases present on your farm.

Most outbreaks of respiratory disease occur within one month of housing with autumn-born calves generally more severely affected.

Some practical tips to help prevent respiratory disease:

- Avoid overcrowding. Reducing stocking density, wherever possible, would improve the respiratory disease situation on most units.

- Optimise timing of vaccinations, so animals have the best immunity during the most challenging period.

- Provide adequate rest, feed and water (especially after shipping).

- Optimise nutritional soundness. Make sure animals receive adequate levels of essential nutrients such as vitamins and minerals.

- Make sure bedding is clean and dry and keep animals as clean and dry as possible.

- Minimise exposure to environmental conditions

- Improve ventilation (see building design below)

- Optimise colostrum management.

- Stress greatly increases an animals’ susceptibility to respiratory disease, so try and minimise this.

- Stressful events, such as disbudding, dehorning and castration, are best separated from the housing event.

- Stressors include weaning, changes of feed, variation in ambient temperature and humidity, and weather. Where possible, try to introduce changes gradually and take measures to minimise the effects

- Handle animals with care. Use low stress handling techniques and reduce and/or minimise pen movements.

Main points of building design

- Air enters below the eaves and exits at the ridge (natural or stack effect whereby spent warm air rises to the ridge outlet to be replaced by fresh air drawn in from below the eaves).

- Minimum of 6 air changes per hour on a still day. Air should appear fresh and free of ammonia or slurry smells when you walk through the shed, especially during still winter nights.

- The ridge opening should be 300 mm (minimum) with a cap at least 150 mm above.

- Buildings should not exceed 20m in width. Multi-span buildings should be avoided.

- Minimum airspace allowances are 10 cubic metres for calves up to 90 kgs.

- Upturned corrugated sheeting on roof with a 25 mm gap.

- Spaced boarding all around the building including gable ends (Netlon polypropylene mesh is also popular).

- Ensure adequate drainage to prevent high humidity. Condensation on the underside of the roof and cobwebs over the outlets are indicators of poor ventilation.

Pre weaned animals do not produce sufficient body heat to drive effective ventilation via the stack effect. For these young animals, draught exclusion, hutches and jackets can be effective.

References

- Taylor G. Animal models of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Vaccine. 2017 Jan 11;35(3):469-480. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.054. Epub 2016 Nov 29. PMID: 27908639; PMCID: PMC5244256.

- Doidge C, Hudson CD, Burgess R, Lovatt F, Kaler J. Antimicrobial use practices and opinions of beef farmers in England and Wales. Vet Rec. 2020 Dec 19;187(12):e119. doi: 10.1136/vr.105878. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32859656.

- Gray D, Ellis JA, Gow SP, Lacoste SR, Allan GM, Mooney MH. Profiling of local disease-sparing responses to bovine respiratory syncytial virus in intranasally vaccinated and challenged calves. J Proteomics. 2019 Jul 30;204:103397. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.103397. Epub 2019 May 27. PMID: 31146050.

- Gray DW, Welsh MD, Doherty S, Mooney MH. Identification of candidate protein markers of Bovine Parainfluenza Virus Type 3 infection using an in vitro model. Vet Microbiol. 2017 May;203:257-266. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.03.013. Epub 2017 Mar 14. PMID: 28619153.

- Illambas J, Potter T, Cheng Z, Rycroft A, Fishwick J, Lees P. Pharmacodynamics of marbofloxacin for calf pneumonia pathogens. Res Vet Sci. 2013 Jun;94(3):675-81. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2012.12.012. Epub 2013 Jan 31. PMID: 23375665.

- Dagleish MP, Bayne CW, Moon GG, Finlayson J, Sales J, Williams J, Hodgson JC. Differences in Virulence Between Bovine-Derived Clinical Isolates of Pasteurella multocida Serotype A from the UK and the USA in a Model of Bovine Pneumonic Pasteurellosis. J Comp Pathol. 2016 Jul;155(1):62-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2016.05.010. Epub 2016 Jun 20. PMID: 27338785.

- Crawshaw WM, Caldow GL. Field study of pneumonia in vaccinated cattle associated with incorrect vaccination and Pasteurella multocida infection. Vet Rec. 2015 Apr 25;176(17):434. doi: 10.1136/vr.102701. Epub 2015 Feb 27. PMID: 25724544.

- Curtis GC, Argo CM, Jones D, Grove-White DH. Impact of feeding and housing systems on disease incidence in dairy calves. Vet Rec. 2016 Nov 19;179(20):512. doi: 10.1136/vr.103895. Epub 2016 Nov 1. PMID: 27803374; PMCID: PMC5299099.

- Taylor G, Wyld S, Valarcher JF, Guzman E, Thom M, Widdison S, Buchholz UJ. Recombinant bovine respiratory syncytial virus with deletion of the SH gene induces increased apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro, and is attenuated and induces protective immunity in calves. J Gen Virol. 2014 Jun;95(Pt 6):1244-1254. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.064931-0. Epub 2014 Apr 3. PMID: 24700100; PMCID: PMC4027036.