What is environmental mastitis?

Environmental mastitis is caused by bacteria which spread primarily outside of the milking parlour, and infection commonly occurs between milkings or during the dry period.

With much focus on controlling and preventing contagious causes of mastitis, the effectiveness of this has led to environmental mastitis pathogens predominating as the main cause of clinical mastitis on most dairy farms. Laboratory data reveals that environmental mastitis now accounts for more than 50% of mastitis case in UK dairy cattle. With this in mind, a specific environmental mastitis control plan in conjunction with your vet, is essential to identifying the specific risk factors and implementing appropriate control methods. Control is essentially targeted at reducing the presence of certain bacteria at the teat opening.

Environmental mastitis bacteria

The two most important and prevalent bacteria in this group are Escherichia coli and Streptococcus uberis. Studies have shown that cases of E. coli are marginally more commonly isolated than those of Strep uberis but this can vary between herds.

E. coli mastitis varies hugely in its severity and presentations, from mild self-limiting cases, to fatal acute toxic mastitis. It is a gram negative bacteria that is present in large numbers in faeces, meaning that organic matter such as bedding and manure are risk factors for infection. Also commonly referred to as coliform mastitis. It often does not respond well to antimicrobials as the symptoms can be related to toxins rather than bacteria itself.

Fig 1: Acute coliform mastitis leads to very sick cows.

Strep. uberis is a gram positive bacteria that is very versatile and can be found throughout the environment and survives and grows in bedding, faeces, pasture and the on skin of cows. It grows well on straw bedding and can be found in frequently used areas at pasture (such as around feed and water troughs or lying areas). It can cause both clinical and sub clinical cases of mastitis and can cause persistent colonisation of the mammary glands without a subsequent rise in somatic cell counts. This usually responds well to penicillin based antimicrobials and no resistance is reported to this category of antimicrobial.

Other bacteria associated with environmental mastitis include Pseudomonas spp. Klebsiella, spp. Proteus and yeasts. Identifying these through bacteriology, culture and sensitivity of milk samples is important, as they may not respond to standard antibiotic protocols and can indicate specific sources for these infections, which will need to be considered.

Fig 2: A pure culture of the organism causing the mastitis is the goal, with its antibiotic sensitivity to narrowly target effective treatment

Being environmental doesn't mean that the bacteria don't spread during milking. Just like with contagious bacteria, infected cows can contaminate the cluster and spread infection to other cows during milking. Of the two bacteria, Strep uberis is the one that spreads more easily during milking, but some strains of E. coli and the other Gram negative bacteria can also readily be transferred between cows. However, unlike contagious bacteria, preventing cow-to-cow spread during milking will not eliminate environmental mastitis. This is because parlour management does not tackle the route from the environmental source to the cow. To control environmental mastitis, a primary focus on environmental hygiene is needed, alongside some parlour management changes.

Fig 3: Good clean housing reduces the risk of environmental mastitis.

Environmental mastitis bacteria

A contaminated environment!

E. coli comes from the gut, so anywhere cow faeces can come into contact with the udder, will provide a potential source of coliform mastitis. Bedding is the most important source, particularly organic bedding where the bacteria can grow and multiply. However, areas around feed or water troughs are also risk areas as slurry and water around these can get splashed onto the udder.

Outside of the udder, Strep uberis is also found in the intestines but, compared to E. coli, it is much more commonly found elsewhere on the cow, particularly the skin. Strep uberis has a fantastic ability to develop outside of the cow; straw and wood based beddings are ideal mediums for this bacteria to multiply on.

Both E. coli and Strep uberis, particularly the latter, can also cause environmental mastitis in cows on pasture as they can survive for months in contaminated wet soiled areas.

Non-organic bedding, such as sand, doesn't support the growth of either E. coli or Strep uberis, so the use of such beds can reduce the risk of mastitis. However, these beds need to be kept clean and replaced fully at least every 6 months, (depending on the system) as there can be more than enough organic material in a single faecal pat to support exuberant bacterial growth.

Infections can occur during the dry period or can be picked up during lactation. Seasonal patterns can be identified with cases of environmental mastitis, which often reflect increased challenge during winter housing months and build-up of unhygienic conditions. Summer months can have hot, humid conditions both inside or outside or time spent at pasture where conditions are less controllable. A crucial time for infection with new environmental mastitis-causing bacteria is the dry period or around calving. Infection during the dry period is often inapparent until the cow develops mastitis after calving. Mastitis cases seen within 30 days of calving are often attributed to infections picked up during the dry period.

Cases during lactation are picked up from the environment when the cow is eating, loafing, lying down, walking in passageways, or introduced during the milking process. In order to control environmental mastitis, we have to focus on environmental management throughout the cow's lactation cycle as well as the non lactation period.

How do you control environmental mastitis?

There are many focus areas which will vary between farms and their individual risks.

Particular attention should be given to controlling hygiene, moisture, temperature and air flow in the cow’s environment. Pathogens associated with environmental mastitis thrive in high humidity conditions, in pooling water and slurry.

a) Hygienic environment

Indoors:

- Avoid keeping cows in damp, dirty conditions. Routine hygiene scoring of cows can help to determine if cows are being kept clean enough. Key areas to check and score are udders, legs, tails and flanks

- Adequate, clean, dry bedding is essential. Replace bedding at least daily, giving deeper areas to where the udder will be located

- Cubicle comfort and design. Ensure clean well-maintained cubicles that are adequate size for the cows. Clean beds down twice daily. Over 90% of cows should be lying in cubicles correctly at one time, if they are of adequate design. Cows lying in passageways will be dirtier and cubicles of incorrect design will result in faecal contamination of udders

- Avoid overcrowding, regardless of housing system. Ensure at least 5% more cubicles than cows. Maintain ideal stocking density rates in straw yards to 12.5m square per cow

- Scrape out alleyways, feeding and loafing areas at least twice daily, to avoid slurry and manure splashing up onto the udder

- If straw yards are used, ensure they are well drained, bedded at least once daily with straw spread evenly and cleaned out fully at least monthly

Fig 4 – Poorly bedded cubicles will increase incidence of environmental mastitis

Pasture:

- Avoid overgrazing and overstocking. A maximum 100 cows per acre over short periods only is advised

- Try to rotate pastures and paddocks at least every 2 weeks to avoid poaching and build up of bacteria in well used areas

- Ensure shade and lying areas (around trees) are large enough to not become too contaminated and overused

- In wet conditions, ensure cows are in well drained paddocks or fence wet areas off.

- Pay particular attention to management around troughs and feeding areas, and entry/exit routes where wet and muddy conditions can predispose to bacterial growth, splashing and dirty conditions. Move troughs regularly, and consider hardcore for gateways and other poached areas.

Fig 5: Good clean pasture can reduce the risk of environmental mastitis

Dry Cows Calving:

- Cows should calve in a clean and dry environment.

- Indoors - ensure plenty of fresh bedding for every cow.

- Outdoors - choose calving paddocks carefully, don't overstock.

General environment considerations:

- Ensure ventilation in sheds is adequate. Poor air flow will result in damp bedding. Good ventilation will decrease bacterial survival time and natural ventilation will ensure the sheds are dry and free of draught. Test the “stack” effect with smoke-bombs. Fans can help in some building designs when enough air movement cannot be achieved (in very long buildings)

- Consider heat stress in time of high temperatures and humidity, and use mechanical ventilation in sheds if needed

- Ensure any stored bedding is kept clean and dry; damp straw and sawdust must not be used as it poses a high mastitis risk

- Ensure clean water is always available, as bacteria will quickly multiply in dirty water

Fig 6 – 90% of cows should be lying in cubicles at any one time

b) Dry cow management

Dry cow therapy will reduce the risk of new environmental infections, particularly in cows with a history of mastitis or high cell counts (see bulletin 8). Using internal teat sealant is the best way of preventing environmental mastitis infections and should be used for every cow at drying off. They can be used alone in cows with low cell counts that don't need an antibiotic, and together with antibiotics in cows that have persistent individual high cell counts in the last 3 months, are currently or chronically infected and are therefore at risk of being infected at drying off. Consult your vet for a specific drying off protocol and mastitis plan that is tailored to your individual farm.

Blanket treatment of every cow with antibiotics is not an appropriate use of antibiotic therapy, increases the likelihood of antibiotic resistance developing, and should only be reserved for those cows that meet the criteria set by your vet. It is also a possible reason for a bulk milk tank failure for antibiotics and can lead to problems for milk processing and human health. Internal teat sealants prevent new infections from the time of insertion, until the cow is milked for the first time (check length of action of teat sealant used is appropriate for the dry period) The new Veterinary Medicine Regulations(2024) specifically highlight that prophylactic routine use of antibiotics at drying off should not occur and the use of these medicines will be monitored at a farm and veterinary practice level.

However, strict adherence to a sterile technique when using any intramammary tubes is vital, to avoid sealing any bacteria into the udder at the time of drying off. Some milk buyers may limit the use of teat sealants so discuss with your vet if there are ways to use this product or if other options - teat dipping with specific teat dips that can dry and form a temporary seal on the teat end, during the dry period or particularly approaching calving.

c) Vaccination

'There are now multiple options for cattle vaccination against specific mastitis pathogens available in the UK, and are a suitable consideration for mastitis control and increasing immunity for some herds. In herds with a significant mastitis problem due to E. coli, the use of a J5 vaccine has been shown to reduce the severity of the disease. A combination vaccine which targets mastitis caused by coliforms, Staph. aureus and other coagulase negative staphylococci is currently available in the UK and may be beneficial on some farms. Farms with specific Strep uberis issues may benefit from a targeted monovalent vaccine approach against Strep Uberis which is also now available for use on UK farms. However, vaccines are only one component of a mastitis control package and a discussion with your vet before implementation is advised; they are not a substitute for good environmental management, and should be used in conjunction with a mastitis control plan, alongside attention to environmental hygiene and other risk factors such as underlying diseases.

d) Good milking routine

Although environmental bacteria spread outside the parlour, good milking management will help to reduce environmental mastitis. So having environmental mastitis does not mean that you need to pay less attention to your milking regime.

- Ensure teats are clean and dry before attaching the cluster with sufficient time to ensure milk let down reflex has occurred. Milking cows with wet udders is likely increase the incidence of environmental mastitis

- Foremilk to detect early mastitis cases

- Keeping teats in good condition, ensuring good milk let down and reducing impacts by good cup removal technique will all reduce the level of environmental mastitis, particularly that caused by Strep uberis.

- Excessive milking machine vacuum can damage teat ends, resulting in increased cases of clinical mastitis – ensure regular and proper maintenance

- Ensure pre-milking teat dipping is part of the milking protocol (See bulletin 7). There are several commercial dips available on the market but you must ensure that you use a dip designed for pre-dipping and allow 30 seconds contact time before you dry the teats with clean, dry paper towel.

Ensure all staff wear gloves and regularly wash them if soiled.

Fig 7: Dirty udders are at risk of environmental mastitis

The environment after milking is very important, as the teat canal can remain open for up to 30 mins after milking. Ensure cows are able to stand and eat straight after milking to allow time for closure before they lie down. Scrape out during milking so walkways and feeding areas are clean. If the cows pass through a foot path after leaving the parlour try to ensure some standing time if possible. Reducing bacterial contact with the open teat canals at this time is very important to reduce chances of pathogens entering up the open teat canal and colonising the udder.

e) Reducing stress; maximising immunity and defences

Reducing stress in a cow’s environment has a variety of beneficial impacts on environmental mastitis.

- Ensuring enough lying, eating and drinking room reduces stress. Cows should have a minimum of 0.7m of feeding space per cow, to reduce queuing and stress from competition. Loafing areas should be clean and of sufficient stress to reduce competition.

- Calm cows produce less faeces and moving at a slower pace result in less faecal contamination and spraying up of faeces.

- Keeping social groups stable reduces stress

- Calm cows have a better milk let down, resulting in better milk flow and less potential teat end damage

- Bring cows in groups to milk reduces waiting time, which reduces stress and standing time. Do not allow cows to stand and wait more than one hour to be milked.

- Try to avoid bottle necks in passageways or at drinking troughs where cows may be stressed

Fig 8 – Avoid cows queuing at the parlour and standing in pooled water

Ensuring good immunity both at the level of the udder and systemically is important in helping cows to fight infection in the udder. Cows in early lactation have reduced immunity, which can be perpetuated by metabolic diseases. Ensuring good nutritional management is essential to addressing these issues.

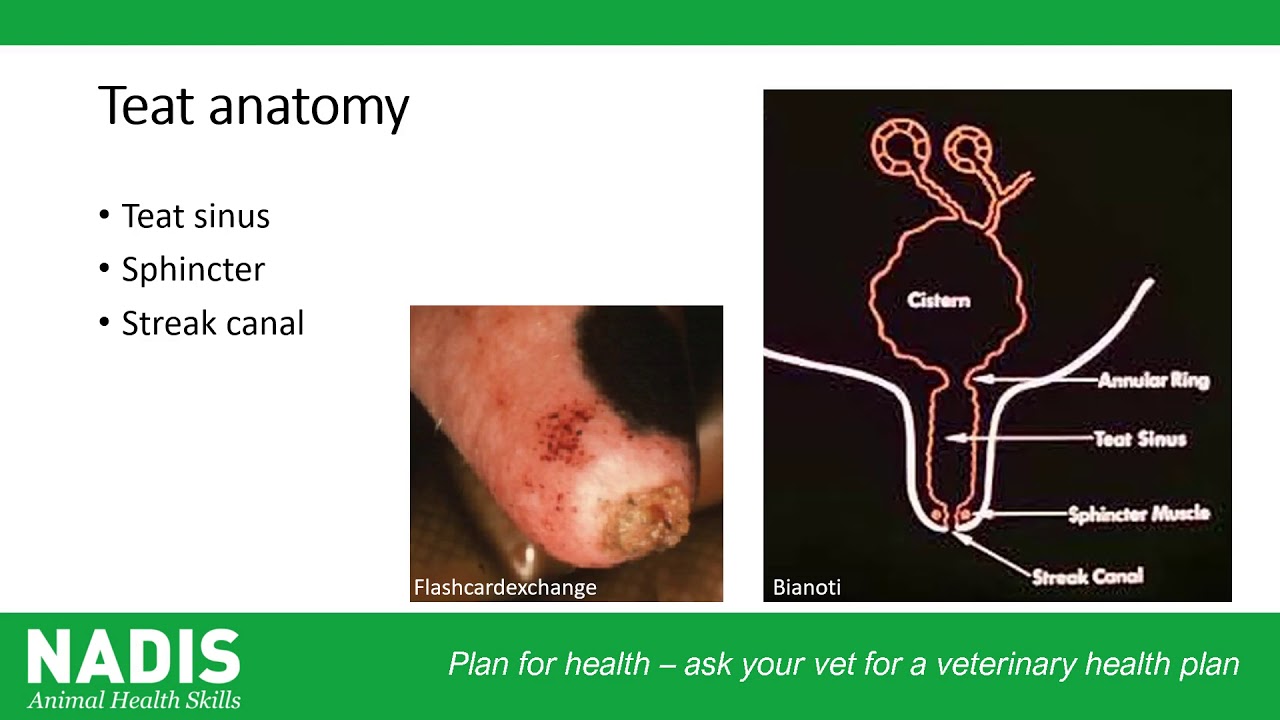

Cows with damaged teats and poor udders have been linked to increased cases of environmental mastitis, as the teat sphincter may not close effectively, making it difficult for individuals to maintain immunity against pathogens entering the teat canal. Check records and if necessary consider removing these cows from the herd.

Routine Teat scoring is an important tool to identify herd issues and to identify if there is a common source. Less than 5% of the herd should have severe teat end hyperkeratosis. More information here

Fig 8 – Avoid cows queuing at the parlour and standing in pooled water

f) Sample taking and recording of cases

Proper mastitis records with good bacteriology are essential to tackling an environmental mastitis problem. Always take sterile milk samples from cows with mastitis before treating them, whether it is a first time or repeat case (include link for sterile milk sampling technique) Samples should be clearly marked with cow ID and affected quarter, and can be frozen for up to 3 months and tested retrospectively if needed. This is especially important in identifying the bacteria involved, their most appropriate and targeted method of antibiotic treatment. Without good information, individualised targeted control programmes cannot be developed for your farm.